Ceremonial VS Culinary Matcha

You’re probably here to find out the difference between ceremonial and culinary matcha. Well, here’s the thing: There really isn’t one.

“Ceremonial matcha” and “culinary matcha” are indicators of intent, rather than strict grades.

Ceremonial is meant to be consumed as a drink, by itself.

Culinary Matcha is meant to be used as an ingredient in cooking, baking, and confectionaries like Matcha Lattes.

Companies will label their drinking matcha as ceremonial, and culinary match as culinary, but it’s important to recognize that while these terms denote how the manufacturer recommends you use their product, they don’t provide information as to the quality of the product.

Because of this, it’s easy to find Matcha from company A that’s labeled as a “ceremonial grade” while company B has higher standards and would label it as a “culinary grade.”

There’s nuance here, of course. Let’s examine that.

It’s (mostly) all Marketing

It would be unfair to say that the terms “ceremonial grade” and “culinary grade” are only marketing terms. After all, they can provide clues.

In general:

You don’t want to use ceremonial matcha in cookies, bakes, and lattes; because the (typically) higher cost is wasted. Not to mention, bitterness from low grades can actually balance out a sweet dessert.

You don’t want to drink most culinary matcha, as it’ll usually be quite unbalanced, astringent, and bitter.

We can also guess that the Culinary grade matcha will be of less quality than the ceremonial. But we still haven’t defined what the quality of Matcha is.

While terms like "culinary" and "Ceremonial" don't tell you much about the quality of a Matcha, it can tell you how the manufacturer recommends you consume it.

Surface Level: The Difference Between Culinary and Ceremonial Matcha

We’ll generalize a bit more here by looking at some expected properties of ceremonial vs culinary matcha. It’s worth reiterating that this is very generalized! From company to company there can be wide ranges of quality between Matcha.

Yet, we can lay out some expectations of what we’d find with a standard culinary Matcha, and a standard ceremonial matcha. We’ll talk about the Matcha itself, rather than the process of making it.

General Notes on Culinary Matcha

With Culinary Matcha, here are some expected properties:

A harsher, bitter taste that stands up better in cooking applications because of its intensity.

A less refined texture, less silky, and less prone to create billowy foam.

Less natural sweetness or savoriness.

A more pale, yellow-toned coloration.

General Notes on Ceremonial Matcha

On the other hand, here are some qualities we’d expect out of the average Ceremonial Matcha.

A silkier mouthfeel that doesn’t leave too much bitterness or astringency.

A more pronounced savoriness and natural sweetness.

More vibrant, electric emerald green.

A higher degree of, and an easier to manifest, small-bubble foam that looks not unlike espresso crema.

Asking the Right Questions

We’ve covered some of the properties of ceremonial versus culinary Matcha, as well as why we have these labels, to begin with (denoting the intended use of the product.) It’s common to use these terms as proxies to denote the quality of a given Matcha.

Being that we want to be more discerning with our Matcha, let’s cover 5 of the many markers that let us judge the true quality of a Matcha.

5 Markers of High-Quality Matcha

1 - Understanding Terroir and Price

When it comes to products like tea, wine, or cigars; the specific location (terroir) the product comes from is a big indicator of its price. After all, your red wine from New Jersey will likely price under a single-estate red wine from Bordeaux.

This doesn’t mean that, when judged side by side, the New Jersey wine will be worse (though, arguably, we could expect that), but it does mean we can expect certain pricing for the bottle from the more renowned location.

The reason I bring this up is that when we want to understand the Matcha we’re drinking and its quality, we can use the location it’s from and its price as signals.

The Pricing Example

Just because something is more expensive, doesn’t mean it’s better of course. What price can do is show us when there’s an inconsistency.

For example, when it comes to the Bordeaux region, we can see that the average “best” bottle of wine (based on a mean of critics’ scores, updated monthly) is anywhere from $400 to $900 a bottle.

Okay, so that gives us some working information. Given that Bordeaux wine production is fairly small (15% of the wine in France, with France accounting for 16% of worldwide wine production), we can expect that if a bottle from this (relatively) limited region is $50, it probably is not a very good wine.

Meanwhile, there are other wine-producing regions around the world where $50 would indicate a high-quality wine.

With Matcha, the same rings true. There are Matcha regions that typically fetch an expected price on the market. If a Matcha from that region is significantly less than the expected price, it could be an indicator that it’s of lower quality.

Pricing Matcha Regions

One of the most legendary regions in the world for Matcha is Uji, Japan. We expect Matcha from the Uji terroir to be superior to Matcha from Vietnam, for example. We can also expect that Matcha from Uji will be more expensive than Matcha from Vietnam.

Understanding the terroir is important. I’d personally prefer a culinary Matcha from Japan over a ceremonial Matcha from China. Despite the fact the “grade” of the Chinese Matcha is higher, for me personally, the location is superior to the labeled grading.

Speaking of Japan, there are many tea-growing regions - all of which have different characteristics that affect the final taste of the tea and have different expected pricing structures. I wrote a blog post about 5 famous Matcha regions in Japan here.

But here’s a little chart with a few high-level tips.

| Region | Notes |

|---|---|

| Uji, Kyoto Prefecture | Most desirable and highest priced Matcha, with limited yearly production. |

| Wazuka, Kyoto Prefecture | Geographically close to Uji, with a higher annual production. |

| Kagoshima Prefecture | 2nd largest tea region with volcanic soil and a more temperate climate allow for a greater range of cultivars. |

| Aichi Prefecture | West of Uji, said to have natural sweetness. |

| Shizuoka | Biggest tea region, steams tea for twice as long as Uji to tame the natural astringency and bitterness. |

Of the above list, Uji Matcha typically demands a higher price on the market, with Shizuoka perhaps being lower. This doesn’t necessarily mean the Uji Matcha is of higher quality than a Shizuoka Matcha, but the terroir is a signal that can clue us in.

With that said, you can get wonderful matcha from any region, but again – our goal is to have a road map. So long as you’re avoiding any Matcha made outside of Japan.

All matcha is steamed as part of the production process. Steaming halts the oxidation process, and also dissolve pectin (which tastes sweet.)

Shorter steaming will preserve more of the “fresh” and nuanced taste, but retain more bitterness/astringency, and dissolve less pectin.

Longer steaming will muddy the tastes, but give a more mild tea with enhanced sweetness.

So, what’s better? Short or Long Steaming? The answer is it’s all about the starting material.

Higher quality terroirs, and more disciplined production methods - will yield plants that have naturally less bitterness and more sweetness. Light steaming works here!

Lower quality terroirs, and shortcuts taken during production, will produce plants that need longer steaming to balance out the material at the cost of retaining more nuance.

2 - Shading Time and Harvest Season

If you’ve ever had good quality matcha, you’ll note it’s typically pretty savory, almost like a dashi broth. That savory taste comes from an amino acid called L-Theanine (the full scoop here.)

When sunlight hits the leaves of the plants, the savory-tasting L-Theanine is converted into astringent-tasting Catechins. So if you want to make a tea that has a more savory taste, you need to block the sun to retard this process.

(Not to mention the shading process also increases the Chlorophyll which makes the resulting Matcha that vibrant, bright green it’s so famous for.)

In Japan, they do this by literally covering the plants with a tarp known as direct shading or a bamboo structure known as a shelf.

Matcha is not the only tea that uses Kabuse during production.

Other covered teas (to make them taste more savory) are Kabusencha and Gyokuro.

Covering the plant takes a lot of time and effort, and how long you keep it covered also depends on the sweet, rich notes. By covering it for a longer period of time you’ll get a more savory tea.

Tea plants for Ceremonial Matcha can be shaded anywhere from 20 to 50+ days and are typically harvested in May or June.

Tea plants for Culinary Grade Matcha will have shorter shading times, or won’t be shaded at all. Typically harvested in July or even as late as October.

Ichibancha vs Nibancha

After the winter, the tea plant sprouts its new buds - full of vigor after having a winter dormant period. This first flush is known as Ichibancha. The first flush contains more than 3 times the savory tasting theanine than the second harvest, about 45 days later known as Nibancha.

For this reason, harvest time is an important factor in the quality of Matcha. Ceremonial Matcha is typically made from the first flush, or Ichibancha, material. Later harvests (second, third, etc) while by their very nature have less sweetness, and savoriness, and include harsher notes.

Nuance, Always Nuance

When it comes to shading duration we can find a lot of variances. For example, there are some wonderful ceremonial Matchas I have come across (and even that we sell) that have a 21-day shading period such as our Kurazumi’s Okumidori Hoshino Matcha, yet our Uji Barista Matcha is a culinary grade with a longer 40-day shading duration.

So duration is shading is not the end all be all. It’s just a factor, one of many, that can paint us a picture of the character of the tea.

3 - Harvest Method

How the tea leaves are harvested has a significant impact on the quality. It used to be that all tea was handpicked, meaning the farmer could pick only the tender shoots.

Avoiding shoots that were sickly or small.

Avoiding stems.

And plucking in a way that does not damage the tea bush.

The problem is that a plucker could only knock out 15-20kg of tea a day. Today, the vast majority of harvesting is done by machine. Machines, like the two-person tea harvesting machine output over 600kg a day. That’s about 3900% more tea.

Handpicking will still put out a higher quality product, yet it’s exceptionally rare to find handpicked tea today in Japan… only account for about 5% of Japanese tea and is generally reserved for higher grades. It’s very improbable to find a hand-picked, culinary-grade Matcha.

4 - Processing and Storage

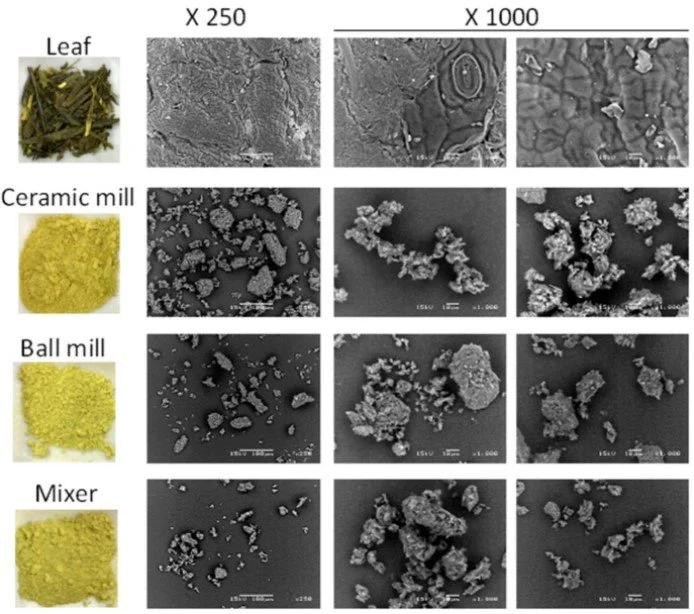

Next up is a short but important element of quality - and that’s how the tea leaves are actually ground up into a powder. You wouldn’t expect this to have such an effect on quality, but it does.

There are two elements at play here: particle size and heat.

First, particle size:

A smoother, more refined Matcha is composed of smaller particles with ragged edges.

“Studies on the physical properties of matcha have revealed differences in particle sizes, shapes, and foaming properties as the result of diverse powdering methods”

Matcha Milling Methods

Here are the various ways to grind matcha and the corresponding particle size. The most traditional way is with an “Ishi Usu”, or stone mill. Here are 3 popular methods:

| Processing Type | Particle Size |

|---|---|

| Ishi Usu (Historic / authentic stone mill) | 10-15 µm, Torn Edges |

| Ceramic Mill | 15 µm, Torn Edges |

| Ball Mill | 23.03 µm, Smooth Edges |

| Mixer | 31.85 µm, Smooth Edges |

Here are some electron microscope scans of the resulting powder (not including the historic stone-mill processing type:)

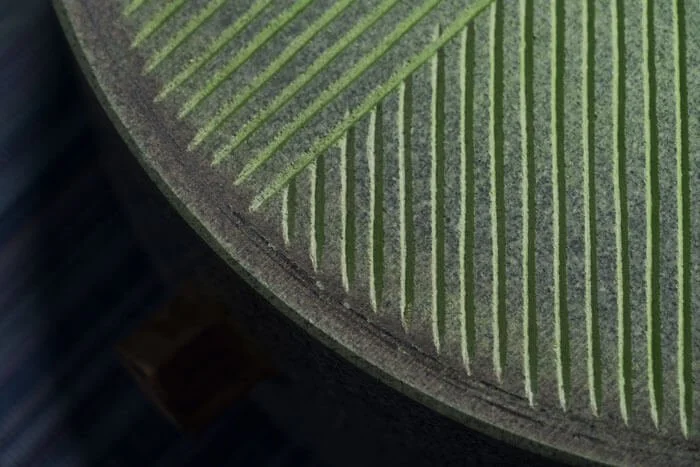

Traditionally matcha is ground using a granite mill. This, as we’ve seen, creates a Matcha powder that is finer than baby powder. The finer the particles, the better the foaming action. When we discuss quality Matcha, we’ll generally prefer Matcha that’s traditionally stone-milled, over more large-scale factory methods like ball mills.

Stones

As far as stones go, there are a few things to discuss because not all stones and mills are created equal. The large traditional stone mills are made from a softer granite and typically mill at 30 revolutions per minute. This doesn’t made a lot of Matcha, by the way:

Stone mills produce about 30 grams of matcha per hour.

Meanwhile, a ball-mill grinder can make over 2,000 grams of matcha per hour!

That’s a 6566% increase in productivity, but at the cost of a higher quality product. This is all relevant because a machine-harvested matcha ground with a ball mill can still be labeled the same “ceremonial grade” as an artisanal hand-picked, traditionally milled Matcha.

As far as stones go, there are many different types available. Online you can find small, hand-turned stones but these are for home use and would not have much commercial application. Larger stones are turned by machines — the added weight of the stones helps create a finer end product.

5 - Proper Storage & Freshness

We’ve touched on some of the elements that can give us an idea of the quality of matcha beyond terms like culinary and ceremonial. Though without proper storage, the potential of the tea is lost. This is especially true of Matcha which is by its very nature a delicate product.

You can see this yourself by putting a scoop of Matcha outside on a sunny day. In less than 10 minutes the vibrant green color will fade, leaving a deadly white powder in its place.

Storing Matcha

When it comes to storing Matcha, there are a few considerations we should keep in mind. Matcha should be:

Away from sunlight.

Airtight.

Cool, away from heat.

Dry, away from humidity.

In some ways, knowing the storage conditions of two separate Matcha is just as important (or not more so) than the ceremonial vs culinary grading label.

It’s worth mentioning here that Matcha can (and should) be kept cold in a refrigerator, under the condition that it’s vacuum-sealed. When you want to open the Matcha to use it, take it from the fridge at room temperature conditions for 24 hours before breaking the sale.

(Otherwise, you risk condensation spoiling the Matcha.) Once the seal is broken, don’t put it back in the fridge.

Freshness

Storage and freshness go hand in hand. The better the storage considerations, the fresher the MAtcha will be when you’re ready to make a bowl of Usucha. Though being that Matcha is (ideally) consumed as soon as possible after it’s been ground, there are some unique points to consider.

You don’t want to grind coffee and let it sit for months or years before drinking it, and it turns out that with Matcha it’s not too different. The difficulty is that Matcha is more difficult, expensive, and specialized to grind than coffee which can be done cheaply in your home.

According to the Japanese Green Tea Association (a wonderful organization for those interested in Japanese tea!), Matcha begins to degrade relatively quickly after grinding even under the most ideal storage conditions.

In fact:

2 months after milling a portion of the fragile Vitamins have degraded.

6 months after milling 30% of the powerful antioxidant catechins have been lost.

This will degrade faster if not stored properly.

We have an incentive then to drink Matcha as fresh as possible. When you try Match that is less than 30 days old you might detect subtle, hard-to-place-with-words, unique freshness. For me, this prized taste is why I started Ooika to begin with!

Freshness isn’t inherent in the quality of tea, but it can clue us into the level of care put into the product. It’s similar to picking a restaurant in a town you’ve never been to - busier usually means higher volume, which generally means fresher products, which can indicate higher quality.

What Matters in a Label

When it comes to labeling of course ceremonial and culinary matter. It’s the Matcha producer’s way of telling us how they want us to use their product. Where things get lost in translation is that people have come to understand these terms as proxies for the quality of the product.

When you are looking at your matcha also consider looking for details such as the region the Matcha is from, the harvest flush (first, second, third?), the shading duration, grinding details...

And we can pay attention to the freshness of the matcha, as well as the storage conditions. All of this information together can paint a more cohesive picture than words like culinary, or ceremonial.

6 Common Ceremonial and Culinary Matcha FAQs

I’ve come across a few common questions on Google about ceremonial and culinary Matcha and wanted to address them real quick. These answers are oversimplified, but straight to the point. Be sure to read the full blog post above to get more nuanced answers.

Why is Ceremonial Matcha better?

Ceremonial Matcha is better because it’s often made from tea leaves that are harvested earlier and shaded longer. Thus Ceremonial Matcha tends to be more savory, sweet, and complex. Culinary matcha is usually quite bitter and is best used in culinary applications like baked goods and lattes.

Is Culinary Matcha as healthy as Ceremonial?

Culinary matcha is not quite as healthy as ceremonial matcha. This is because ceremonial matcha is typically harvested earlier in the season and shaded longer. Young, deeply shaded tea leaves have higher L-Theanine (relaxation-inducing amino acid) and Catechin (antioxidant) levels. Both are healthy, though!

Can you use Ceremonial-grade Matcha for cooking?

Yes, you can use ceremonial matcha for cooking. Culinary matcha is typically more bitter and strong, which holds up better in cooking and with other flavors - not to mention more affordable. If you cook with ceremonial matcha, the flavor might be a bit light and hard to detect - but it’s OK to use!

Does Starbucks use Ceremonial grade Matcha?

No, Starbucks does not use ceremonial Matcha. In fact, the Starbucks "Matcha" powder is at least 51% pure sugar... meaning it's technically not even matcha! It's powdered sugar with a smaller amount of culinary Matcha added to it. Starbucks Matcha has very little in common with true matcha.

Why is Ceremonial Matcha so expensive?

Authentic matcha is expensive because of the high degree of effort and skill that goes into its production. Leaves must be shaded from the sun for weeks, steamed, de-veined, de-stemmed, and slowly ground with expensive stone mills. Some Matcha is even hand-picked, adding to the cost.

Is Ceremonial Matcha organic?

Ceremonial Matcha can be organic, but most Matcha from Japan is typically not organic. There is nearly no demand for organic tea domestically in Japan as their farming standards are higher. Organic Matcha is exclusively for exporting out of Japan and may be of lower overall quality.

Getting to Grinding

At face value, the question of culinary and ceremonial Matcha is pretty simple: ceremonial is meant to be drunk with water, while culinary is best used as an ingredient in foods and sweetened drinks.

When we ask what’s the difference between culinary and ceremonial Matcha though, we’re generally looking to understand the differences in quality of the two grades. This takes a bit more nuance to pick apart.

My best advice is to look at the labeling of the Matcha to get a sense of its quality. At Ooika, this is something we focus on: our Matchas are clearly labeled with as much detailed information as we can provide.

We’re also proud to operate one of the few traditional Japanese Ishi-Usu Matcha grinding mills in the United States to ensure the most freshness possible. You can visit our shop to buy fresh ground Matcha here, and experience both our culinary and ceremonial grades!